When, in 2005, Philips decided to open its research facilities in Eindhoven and turn it into an area for open innovation, they contacted R&D centres imec in Leuven, Belgium and TNO in the Netherlands. Philips felt a research facility to be indispensable for the success of the open innovation campus. And Philips expected that a partnership between these two leading R&D centres – working on autonomous sensor-based microsystems and systems-in-foil (flexible electronics) technology – would bring the synergy they were looking for.

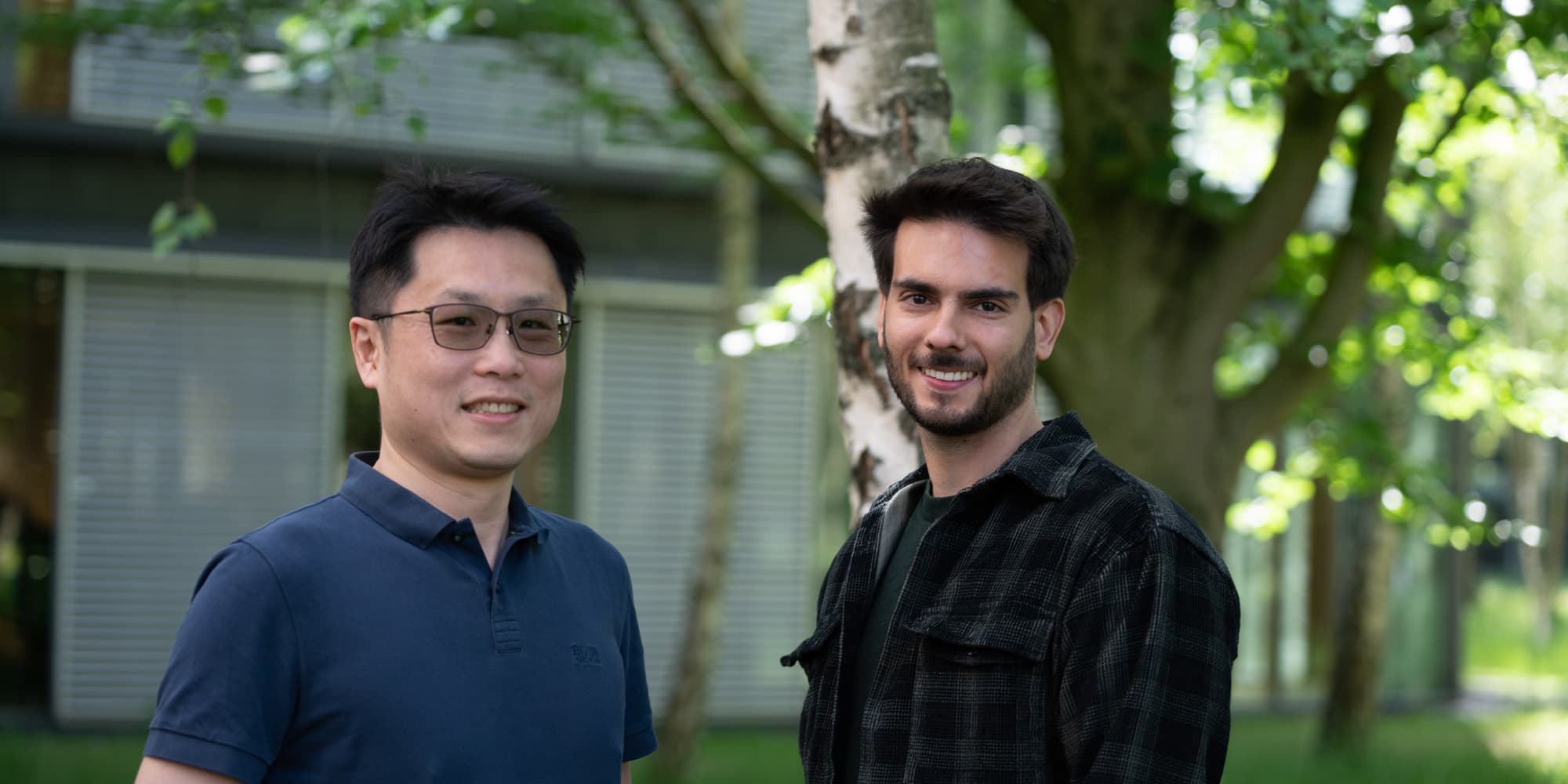

Now 15 years later, Holst Centre boasts over 180 employees from 28 nations who, together with 56 industrial partners innovate and connect, to develop breakthrough technology solutions. Founding fathers of Holst Centre Jo De Boeck (imec) and Jaap Lombaers (TNO) look back on what it took to establish a successful joint research centre.

Creating value-adding synergies in a joint research centre

De Boeck: ‘Philips was definitely the matchmaker between imec and TNO! Philips believed that we were the perfect match to set up a research centre based on our combined technologies. We would be able to benefit from each other’s know-how to enable ground-breaking innovations.’

Lombaers: ‘Their idea for what was to become the High Tech Campus was a visionary one. They rightly believed that the added value of such a campus would be in creating a collaborative environment. This would be the basis of an eco-system in which innovation was to be the driving force.’

‘In the same vein, Philips believed that by partnering in a research- and innovation centre, TNO and imec would together be able to create new value adding synergies and solutions. Imec would contribute know-how on autonomous sensor-based microsystems. Whereas TNO would bring our expertise in the field of flexible electronics technology.’

‘Our respect for Philips’ visionary idea is reflected in the name we chose for our new facility: Holst Centre. Gilles Holst is considered the founder of research at Philips and is one of the pioneers of industrial research in the Netherlands.’

Research within a lively eco-system

De Boeck: ‘Of course, it took time and effort for both imec and TNO to define the partnership and the strategic positioning of the joint initiative. The broad scope was in line with Philips’ MiPlaza centre for micro- and nano technology. But from the outset, we realised that we would be able to make a far bolder statement by focusing and building on specific synergistic technologies. In doing so, we aspired to become the go-to place for innovation on the roadmaps mentioned by Jaap.’

‘We defined three key aspects that were - and still are - essential for the type of research we had in mind. Research that is constantly ahead of the market, offering innovative solutions to meet future societal demands.’ These 3 key aspects were:

- Close working partnerships with industry in a thriving eco-system

- Good complementarity and partnerships with the existing innovation and research ecosystem

- Governmental support and funding at both local, regional and national level

‘The industrial pool that we needed was present in the so-called Brainport area in Eindhoven and we had unique, promising technologies. In addition, we were lucky as far as governmental funding was concerned: it turned out to be the perfect timing for such an initiative. Policymakers were convinced that government funding was essential for staying at the forefront of innovation and maintaining a competitive edge in the global marketplace.’

Research roadmaps and open innovation

Lombaers: ‘So there we found ourselves one day – an enthusiastic team – operating from spanking new offices on the High Tech Campus, seated between the cardboard boxes. It felt like we had just embarked on the adventure of a lifetime. Except that we first had to invest some considerable effort into enabling that adventure.’

De Boeck: ‘That’s right! So, for starters, and importantly, we drew up research roadmaps. We were adamant (and still are to this day) to have a clear understanding of where we wanted to be heading. In fact, such roadmaps are subject to constant tweaking and fine-tuning, in close collaboration with our industrial partners. In this way we keep them in sync with what is happening outside in the ‘real’ world. We need to constantly ask the question whether what we are developing, offers a viable and value-adding solution to real-life issues that need to be resolved?’

Lombaers: ‘The whole idea behind open innovation is to enable faster, cheaper and more effective innovation by bringing players together. In this way, time to market for new products can be speeded up considerably. Of course, there was an initial fear from industry regarding the open innovation model. Were they going to lose their know-how to the competition?’

‘But, Philips backed up this vision and after signing up a second interested party, more industry players soon were interested to join.’

‘Companies overcame their initial hesitations, partly due to the fear of missing out. More, importantly, Holst Centre fulfils a need: the speed of innovation is just too fast and the complexity too high for individual companies to do all R&D themselves.’

‘The perception soon grew that the eco-system around Holst Centre offers unique opportunities to not only develop innovative technologies, but to translate these into viable products that can be successfully brought to market. And because we had sound research roadmaps in place, we were able to put in place a robust research offering.’

Re-evaluating research

De Boeck: ‘From the outset we’ve been – and will continue to be – in an ongoing discussion regarding our role as not-for-profit research institute. Yes, we have the roadmaps, but how far should and can we go in pre-competitive and generic research? And at what point do we stop with our proof-of-concept activities, leaving further development to industry?’

Lombaers: ‘Similarly, we need to constantly evaluate if our research and innovations are still relevant. I believe this has been important to the success of Holst Centre: that we dare to keep re-evaluating the relevance of our research and innovations in the real world.’

‘For instance, in the first ten years of Holst Centre, we invested much in developing so-called OLED lighting technology. Philips and many other industrial players were extremely interested and we were convinced of the benefits and potential of this technology for lighting applications. Until we were totally eclipsed by LED lighting technology.’

‘In the meantime, OLED has become the leading technology in another domain: the display industry. The lesson learned here, was that investing so much time and manpower in just one technological solution poses a risk. On the other hand, thanks to this focus we acquired unique and valuable know-how that we were able to put to good use in other applications such as displays and sensors.’

De Boeck: ‘Yes, that’s also part of open innovation at Holst Centre. Having a roadmap in place is one thing, daring to re-assess your ambition and redirect resources is the key to sustainability. Re-assessing is what we do all the time.’

Innovation: contributing to a healthier and more sustainable world

Lombaers: ‘Thanks to the knowledge transfer within the eco-system in which we operate, it is possible for us to finetune our research and innovation to match pressing societal issues. What’s more, by leveraging each other’s know-how, we can take technologies to the point where they are ready for market.’

De Boeck: ‘It puts us in a position where we are able to build relevant, innovative solutions to tackle real life challenges. The focus since the start has been on state-of-art research with impactful innovation in mind.’

Innovation: driven by the human factor

De Boeck: ‘From the very beginning we have had a focus to attract top talent to Holst Centre. The drive to develop technology that can help us face societal challenges and contribute to a healthier and more sustainable world is something which appeals greatly to the current generation of ambitious innovators.’

Lombaers: ‘Innovation is something that is done by people. It’s their interest in creating sustainable solutions that is the driving force behind our success. Also with regard to our pool of talented researchers and technicians, we experience the benefits of creating and sustaining an innovation eco-system. We proudly see many of our people move to industry after a number of years at Holst Centre. It’s the most ‘physical’ form of knowledge transfer! Similarly, researchers from industry are eager to make the move to us. This provides us not only with value-adding technical knowledge, but also with further insights in industrial needs, markets and applications.’

Dutch version

Holst Centre – 15 jaar open innovatie

De succesvolle weg naar een onafhankelijk onderzoeks- en innovatiecentrum

Toen Philips in 2005 besloot de deuren van zijn onderzoekslaboratoria in Eindhoven te openen en er een centrum voor open innovatie van te maken, nam het bedrijf contact op met de R&D-centra imec in het Belgische Leuven en TNO in Nederland. Philips zag een onderzoekscentrum als onontbeerlijk voor het succes van de open innovatie-campus. Zij verwachtten dat een samenwerking tussen deze twee toonaangevende R&D-centra – de een werkend aan autonome sensor-gebaseerde microsystemen, de ander aan systems-in-foil (flexibele elektronica) technologie – de synergie zou opleveren waar ze naar op zoek waren.

Nu, 15 jaar later, heeft Holst Centre meer dan 180 medewerkers uit 28 landen. Samen werken zij met 56 industriële partners aan innovaties voor het ontwikkelen van baanbrekende technologische oplossingen. De ‘founding fathers’ van Holst Centre, Jo De Boeck (imec) en Jaap Lombaers (TNO), blikken terug op de ingrediënten om een succesvol gezamenlijk onderzoekscentrum op te zetten.

Waardetoevoegende synergieën in een gezamenlijk onderzoekscentrum

De Boeck: ‘Philips was absoluut de matchmaker tussen imec en TNO! Philips geloofde dat wij de perfecte match waren om een onderzoekscentrum op te zetten op basis van onze gecombineerde technologieën. We zouden van elkaars knowhow kunnen profiteren om baanbrekende innovaties mogelijk te maken.’

Lombaers: ‘Hun idee voor wat uiteindelijk de High Tech Campus zou worden, was visionair. Ze geloofden, en terecht, dat de toegevoegde waarde van zo’n campus zou zitten in het creëren van een omgeving voor samenwerking. Dit moest de basis vormen van een ecosysteem waarin innovatie de drijvende kracht zou worden.’

‘In lijn hiermee, was Philips er ook van overtuigd dat TNO en imec, door samen te werken in een onderzoeks- en innovatiecentrum, gezamenlijk nieuwe, waardetoevoegende synergieën en oplossingen zouden kunnen creëren. Imec zou de knowhow over autonome sensor-gebaseerde microsystemen inbrengen en TNO de expertise op het gebied van flexibele elektronica.’

‘Ons respect voor het visionaire idee van Philips zie je terug in de naam die we hebben gekozen voor onze nieuwe onderzoeksfaciliteit: Holst Centre. Gilles Holst wordt beschouwd als de grondlegger van het onderzoek bij Philips en is een van de pioniers in industrieel onderzoek in Nederland.’

Onderzoek binnen een levendig ecosysteem

De Boeck: ‘Uiteraard kostte het zowel imec als TNO tijd en moeite om de samenwerking en de strategische positionering van het gezamenlijke initiatief te bepalen. Een brede scope was in lijn met Philips’ MiPlaza, een onderzoekscentrum voor micro- en nanotechnologie. Maar vanaf het begin beseften we dat we een veel gedurfder en krachtiger statement konden maken door te focussen en voort te bouwen op specifieke synergetische technologieën. Daarmee wilden we dé go-to place worden voor innovatie in de vastgestelde roadmaps.’

‘We hebben drie kernaspecten gedefinieerd die essentieel waren – en nog steeds zijn – voor het soort onderzoek dat we voor ogen hadden. Onderzoek dat steeds vooruitloopt op de markt en innovatieve oplossingen biedt om aan toekomstige maatschappelijke vragen en eisen te voldoen.’

Deze drie kernaspecten zijn:

- Partnerschappen voor nauwe samenwerking met de industrie in een bloeiend ecosysteem

- Goede complementariteit en partnerschappen met het bestaande innovatie- en onderzoeks-ecosysteem

- Overheidssteun en financiering op zowel lokaal, regionaal als nationaal niveau

‘De industriële pool die we nodig hadden, was aanwezig in het zogeheten Brainport-gebied in Eindhoven en we hadden unieke, veelbelovende technologieën. Bovendien hadden we geluk wat de overheidsfinanciering betreft: de timing voor een dergelijk initiatief bleek perfect te zijn. Beleidsmakers waren ervan overtuigd dat financiering door de overheid essentieel was om op innovatiegebied voorop te blijven lopen en een concurrentievoordeel te behouden op de mondiale markt.’

Research roadmaps en open innovatie

Lombaers: ‘Dus op een dag zaten we daar dan: een enthousiast team, opererend vanuit een spiksplinternieuw kantoor op de High Tech Campus, tussen de kartonnen dozen. Het voelde alsof we zojuist aan het avontuur van ons leven waren begonnen. Alleen moesten we eerst nog flink aan de bak om dat avontuur mogelijk te maken.’

De Boeck: ‘Nou, absoluut! Dus om te beginnen – en heel belangrijk – hebben we de research roadmaps opgesteld. We waren erop gebrand, en dat zijn we nog steeds, een duidelijk beeld te hebben van waar we naar toe wilden. Sterker, deze roadmaps worden voortdurend bijgesteld en verfijnd, in nauwe samenwerking met onze industriële partners. Op deze manier zorgen we dat ze blijven aansluiten bij wat er buiten in de ‘echte’ wereld gebeurt. We moeten ons steeds de vraag stellen of wat we ontwikkelen een haalbare en waardetoevoegende oplossing biedt voor het oplossen van maatschappelijke problemen.’

Lombaers: ‘Het hele idee achter open innovatie is dat je sneller, goedkoper en effectiever kunt innoveren door spelers bij elkaar te brengen. Op die manier kan de time-to-market voor nieuwe producten aanzienlijk worden versneld. Natuurlijk stond de industrie aanvankelijk huiverig tegenover het open innovatiemodel. Zouden ze hun knowhow niet kwijtraken aan de concurrentie?’

‘Maar, Philips stond volledig achter deze visie en nadat een tweede geïnteresseerde partij was binnengehaald, waren al snel meer spelers uit de industrie geïnteresseerd om mee te doen.’

‘Bedrijven stapten over hun aanvankelijke twijfels heen, deels uit angst om iets te missen. En belangrijker nog, Holst Centre voorziet in een behoefte: voor individuele bedrijven is de snelheid van innovatie gewoon te hoog en de complexiteit te groot om alle R&D zelf te doen.’

‘Al snel groeide het besef dat het ecosysteem rond Holst Centre unieke kansen biedt om niet alleen innovatieve technologieën te ontwikkelen, maar deze ook te vertalen in levensvatbare producten die met succes op de markt gebracht kunnen worden. En omdat we gedegen research roadmaps hadden, konden we een robuust onderzoeksaanbod neerzetten.’

Blijven evalueren

De Boeck: ‘Vanaf het begin hebben we steeds de discussie gevoerd – en we blijven dat doen – over onze rol als not-for-profit onderzoeksinstituut. Ja, we hebben de roadmaps, maar hoe ver moeten en kunnen we gaan in pre-competitief en generiek onderzoek? En op welk punt stoppen we met onze proof-of-concept activiteiten en laten we de verdere ontwikkeling over aan de industrie?’

Lombaers: ‘Zo ook moeten we voortdurend evalueren of ons onderzoek en onze innovaties nog steeds relevant zijn. Ik denk dat dit belangrijk is geweest voor het succes van Holst Centre: dat we niet bang zijn om de relevantie van ons onderzoek en onze innovaties in de echte wereld steeds opnieuw tegen het licht te houden.’

‘Om een voorbeeld te geven: in de eerste tien jaar van Holst Centre hebben we veel geïnvesteerd in de ontwikkeling van zogeheten OLED-verlichtingstechnologie. Philips en veel andere spelers uit de industrie waren uitermate geïnteresseerd en we waren overtuigd van de voordelen en het potentieel van deze technologie voor verlichtingstoepassingen. Totdat we volledig werden ingehaald door LED-verlichtingstechnologie.’

‘Intussen is OLED de leidende technologie geworden binnen een ander domein: de display- industrie. De les die we hier hebben geleerd, is dat zoveel tijd en mankracht investeren in slechts één technologische oplossing risico’s met zich meebrengt. Aan de andere kant hebben we dankzij deze focus unieke en waardevolle kennis opgedaan, die we goed hebben kunnen gebruiken in andere toepassingen, zoals displays en sensoren.’

De Boeck: ‘Ja, ook dat hoort bij de open innovatie in Holst Centre. Een roadmap hebben is één ding, maar je ambitie opnieuw durven beoordelen en resources herverdelen en inzetten is de sleutel tot duurzaamheid. Opnieuw evalueren en beoordelen; dat doen we continu.’

Relevante oplossingen voor echte problemen

Lombaers: ‘Dankzij de kennisoverdracht binnen het ecosysteem waarin we opereren, kunnen we ons onderzoek en onze innovatie verfijnen en afstemmen op prangende maatschappelijke vraagstukken. Bovendien kunnen we, door elkaars knowhow optimaal te benutten, technologieën zo ver brengen dat ze klaar zijn voor de markt.’

De Boeck: ‘Dit brengt ons in een positie waarin we relevante, innovatieve oplossingen kunnen ontwikkelen om echte, bestaande problemen aan te pakken. Vanaf de start heeft de focus gelegen op state-of-the-art research met impactvolle innovatie.’

Gedreven toptalent

De Boeck: ‘En vanaf het allereerste begin hebben we ons gericht op het aantrekken van toptalent voor Holst Centre. De drive om technologie te ontwikkelen die ons kan helpen maatschappelijke problemen aan te pakken en bij te dragen aan een gezondere en duurzamere wereld, is iets dat de huidige generatie ambitieuze innovators enorm aanspreekt.’

Lombaers: ‘Innovatie is iets dat door mensen wordt gedaan. Het belang dat zij hechten aan het creëren van duurzame oplossingen, is de drijvende kracht achter ons succes. Ook als het gaat om onze pool van getalenteerde onderzoekers en technici, ervaren we de voordelen van het creëren en in stand houden van een innovatie-ecosysteem. Met trots zien we veel van onze mensen na een aantal jaren bij Holst Centre overstappen naar het bedrijfsleven. Dat is de meest ‘fysieke’ vorm van kennisoverdracht! Omgekeerd maken ook de onderzoekers uit de industrie graag de overstap naar ons. Dat levert ons niet alleen waardetoevoegende technische kennis op, maar geeft ons ook meer inzicht in behoeften van de industrie, markten en toepassingen.’

Jo De Boeck joined the company in 1991 after earning his Ph.D. from KU Leuven. He has held various leadership roles, including head of the Microsystems division and CTO. He is also a part-time professor at KU Leuven and was a visiting professor at TU Delft. Jo oversees imec's strategic direction and is a member of the Executive Board.

Jaap Lombaers is responsible for TNO's knowledge management (including management of the Early Research Programs by which TNO builds new R&D propositions across its departments and units) and for the development of TNO's strategic partnerships with industry, universities and governments.

Published on:

15 October 2021