In this series of Moonshot interviews, imec Netherlands talks to experts about the impact of nanotechnology on our future society. Melanie Peters, director of the Rathenau Instituut, and Kathleen Philips, General Manager at imec within Holst Center, look together at the ethical dilemmas of digital technologies in our society.

Dutch people who can still remember the introduction of the personal computer, probably remember the name Rathenau. Gerhart Rathenau gained national fame in 1979 with his committee that had to map out the social consequences of microelectronics and the computer chip. Rathenau, himself an enthusiastic scientist - he was director of the Physics Lab at Philips - wanted to shake up the Netherlands and prepare for the impact of the chip and the PC. In his view, they would digitize society to a great extent. The discussion initiated by Rathenau led to the establishment of NOTA in 1986, which was tasked with researching the social meaning of technology and science. NOTA was later renamed the Rathenau Instituut. More than 40 years after the Rathenau Commission, our society has indeed been extensively digitized. Moreover, we are on the eve of a new evolution; the deep-tech wave. Disciplines and technologies such as AI, IoT, molecular engineering, biotech and robotization together provide disruptive innovations that we as humans have to learn to live with. Is it time for a wake-up call again?

“What does technology contribute to?”

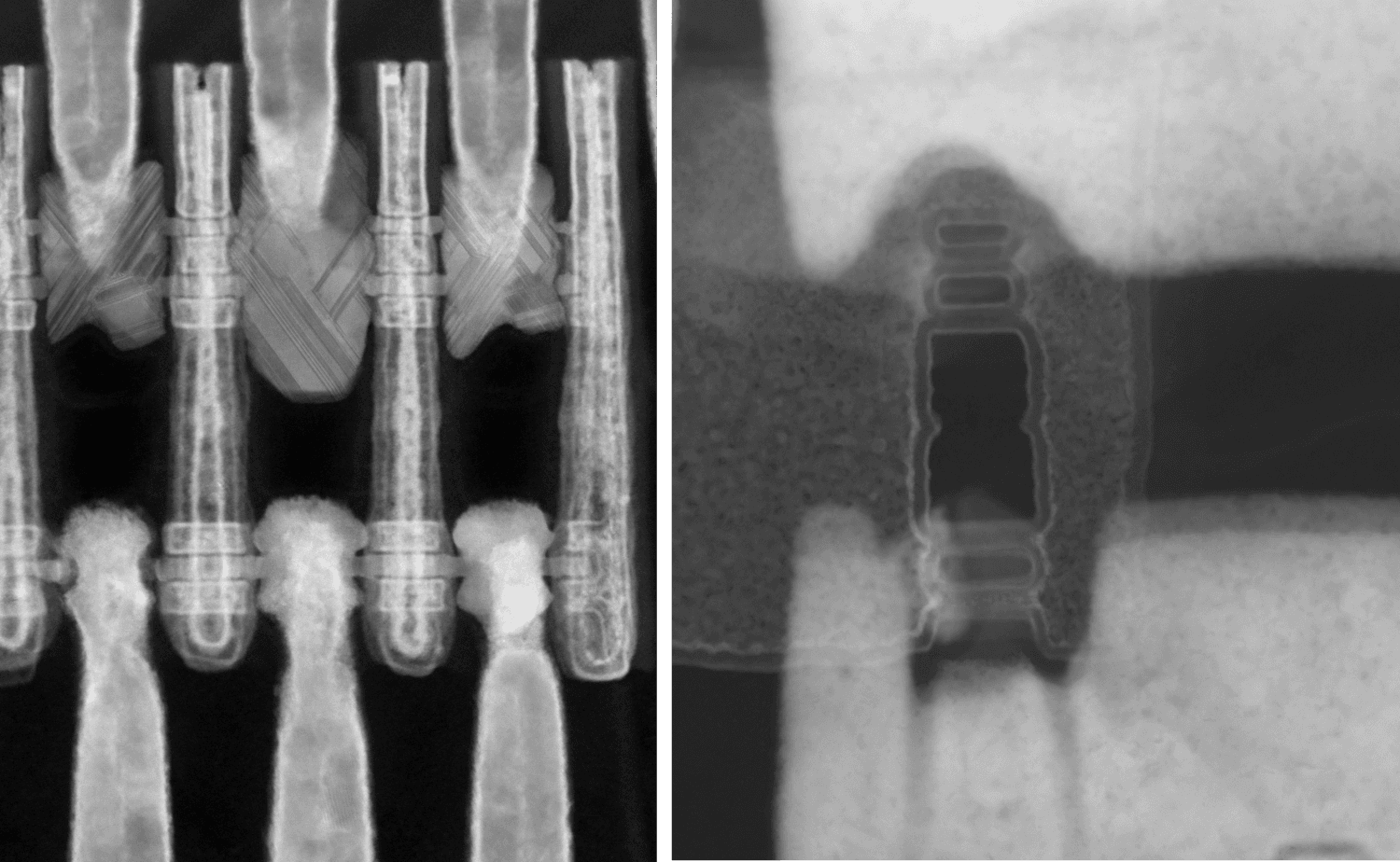

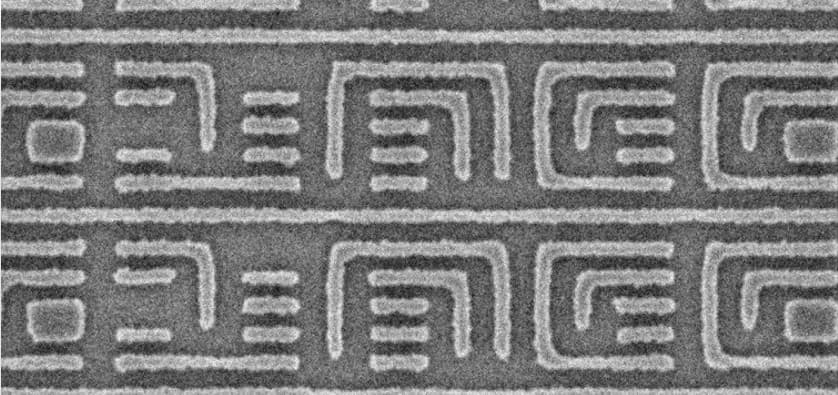

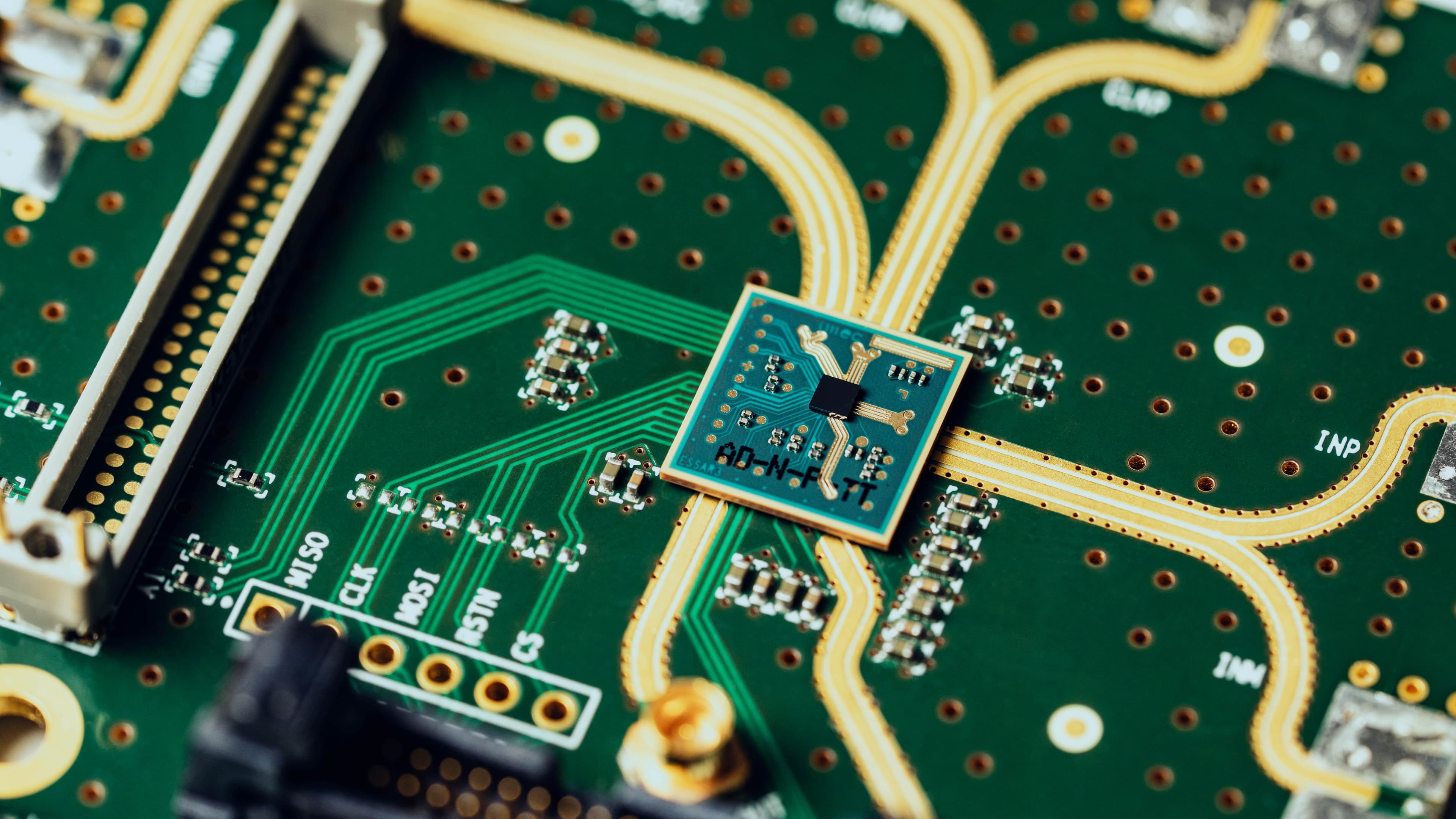

Melanie Peters herself has a scientific background and has been director of the Rathenau Instituut since 2015. “I am driven by the empowering responsibility I feel with regard to technology. That it is used for everyone's interest, so that innovation never misses its social goal.” Her interlocutor, Kathleen Philips, has devoted her scientific career to the development of microelectronics. “I find it exciting to be at the forefront of technology. But I agree with Melanie that you should always get support first. We do not conduct research for the pure sake of research. Technology always starts with a social discussion, because you have to understand very well where it lands and to what it contributes. Otherwise you run the risk of making wrong choices. We do this by talking to the customer of the customer; we call that the ‘voice of customer’ at imec.” Imec believes that technology - and nanotechnology in particular - can make an important contribution to our quality of life. In many areas, but especially in healthcare. Kathleen: “In the first place because we can make illness partly manageable. For example in the case of Parkinson's or a cerebral infarction. With the help of wireless microchips, we can better map the brain and intervene in a very targeted manner with stimulation or medication. That is not only physical gain, but also mental. What we call ‘patient to person’ means that with a condition you can actively participate in society again. That enriches my life. Just like my phone, which gives me a wealth of information and world views. Man and telephone are already - in a figurative sense - fused with each other. This will continue, when chip technology can also enhance my body if it doesn’t function properly.”

“My first concern is quality of life, what can we add to that? For a kidney patient, the promise of an implantable artificial kidney is lifechanging” - Kathleen Philips

“Put collective values first”

When we look at the fusion of man and machine, it’s no longer science fiction. Which ethical boundaries do we have to take into account? Melanie: “Nanotechnology is one of the so-called NBIC technologies, or human-enhancing technologies. They have the potential to radically change the world and our humanity. Our challenge will be not to think in terms of individuals, but also to talk about the collective human values that we want to safeguard as a society. You don't want to withhold solutions from anyone, but at the same time you want to make clear for whose problem this is a solution. In many cases you rely on old ethics. For example, someone must be able to decide for himself: I don't need it, and at the same time have the right to use it. It’s about the emancipation of ordinary citizens compared to experts. At Rathenau Instituut we use the term ‘technological citizenship’. This means that citizens really have a say. They can think together about what technology is needed, and how it can be developed and implemented. It’s about how technology can serve people, instead of asking people and society to continiously adapt to technology.” Kathleen: “My first concern is quality of life, what can we add to that? For a kidney patient, the promise of an implantable artificial kidney is lifechanging. The prospect of having a chip implanted in our body may sound threatening for a lot of people. But what if this chip can actually restore certain bodily functions, and that as a result they no longer have to take large amounts of medication every day? I do notice that the corona crisis has brought a number of those technology-ethics debates to the surface.”

New human rights

About five years ago, the Rathenau Instituut came up with the proposal to introduce two new human rights. Melanie: “The first one is the right not to be measured, analyzed or coached. Monitoring can be a positive thing, but it can also limit you in certain ways. That’s why we believe that there should also be situations and places where you can’t be monitored. We also advocated the right to meaningful human contact. For example within healthcare, but also when the government makes an important automated decision. This also means that in our opinion robots should never replace human relationships, only improve them. Our advice was ultimately adopted by the Council of Europe. And since then the discussion has returned over and over again.” Kathleen: “Human contact is an important point. We are convinced that with technology we can make much better use of our healthcare professionals. I would even go so far as to argue that nanotechnology is the only solution if you want to make healthcare scalable and regain focus on the doctor-patient relationship, specifically for tasks that cannot be solved with a chip or technology.” Melanie: “You have to consciously use it for people who benefit from it, putting technology at the service of people. Together with healthcare professionals you need to carefully look for added value. Technology will not replace doctors, but it may offer instruments that would otherwise not be available to them.”

“At Rathenau Instituut we use the term ‘technological citizenship’. This means that citizens really have a say. They can think together about what technology is needed, and how it can be developed and implemented” - Melanie Peters

“An improved quality of life”

Finally: what would Melanie’s and Kathleen’s ideal digitalized society look like in 20 years, what’s their moonshot? “Nanotechnology will then form a crucial part of the solution to global challenges, especially in healthcare,” says Kathleen. “With nanotechnology we will soon be able to not only restore functions, but also to improve or adapt human capacities and properties. I see an improved quality of our daily life.” Melanie also sees promising applications of nanotechnology: “For example in urban agriculture and local food production, for optimizing crop yields. In the energy sector, in order to be able to coordinate supply and demand. I also believe in ‘citizen science’, where technology will help us share knowledge. Instead of top-down dashboard models in which the government collects our data, we again have access to our data ourselves. And, I would like to challenge imec that with every innovation you question the underlying problem: what are we trying to solve? Because, as Gerhart Rathenau noted in his time: we sometimes forget that technology is not going to solve everything, but it is not going to mess up everything either.”

Disclaimer photography: portraits were taken in compliance with COVID-regulations and edited for publication purposes.

In Memoriam: Melanie Peters

It is with great sadness that we learned of the passing of Melanie Peters, director of the Rathenau Instituut, on 11 August. Only a few months ago, we had the pleasure to interview Melanie for this Moonshot article, together with Kathleen Philips, General Manager of imec at Holst Center. With great passion and energy Melanie emphasized the human and social aspect of technology: “I am driven by the empowering responsibility I feel with regard to technology. That it is used for everyone's interest, so that innovation never misses its social goal.”

Our thoughts go out to her family and loved ones.

Dutch Version

Hoe kan nanotechnologie onze kwaliteit van leven verbeteren?

In deze serie Moonshot-interviews gaat imec Nederland in gesprek met experts over de impact van nanotechnologie op onze toekomstige samenleving. Melanie Peters, directeur van het Rathenau Instituut, en Kathleen Philips, General Manager van imec binnen het Holst Centre, kijken samen naar de ethische dilemma’s van digitale technologieën op onze samenleving.

Nederlanders die zich de introductie van de personal computer nog kunnen herinneren, kennen waarschijnlijk nog de naam Rathenau. Gerhart Rathenau kreeg namelijk in 1979 landelijke bekendheid met zijn commissie die de maatschappelijke gevolgen in kaart moest brengen van micro-elektronica en de computerchip. Rathenau, zelf een bevlogen wetenschapper – hij was directeur van het Natuurkundig Lab van Philips – wilde Nederland wakker schudden en voorbereiden op de impact van de chip en de pc. Die zouden in zijn ogen de samenleving verregaand digitaliseren. De discussie die Rathenau op gang bracht, leidde in 1986 tot de oprichting van NOTA, dat als taak krijgt om de maatschappelijke betekenis van technologie en wetenschap te onderzoeken. NOTA werd later omgedoopt in het Rathenau Instituut. Ruim 40 jaar na de Commissie Rathenau is onze samenleving inderdaad verregaand gedigitaliseerd. Bovendien staan we aan de vooravond van een nieuwe evolutie, de deeptech-golf. Disciplines en technologieën als AI, IoT, moleculaire engineering, biotech, en robotisering zorgen samen voor disruptieve innovaties waar we als mens mee moeten leren leven. Is het opnieuw tijd voor een wake-upcall?

‘Waar draagt technologie aan bij?’

Melanie Peters heeft zelf een wetenschappelijke achtergrond en is sinds 2015 directeur van het Rathenau Instituut. “Ik word gedreven door de emanciperende verantwoordelijkheid die ik voel ten aanzien van technologie. Dat het voor ieders belang wordt ingezet, zodat innovatie nooit haar maatschappelijke doel voorbijschiet.” Haar gesprekspartner Kathleen Philips wijdde haar wetenschappelijke carrière tot nu toe aan de ontwikkeling van micro-elektronica. “Ik vind het spannend om in de voorhoede van de technologie te werken. Maar ik ben het met Melanie eens dat je altijd eerst draagvlak moet krijgen. We doen geen onderzoek voor het onderzoek. Technologie begint altijd met een maatschappelijk discussie, omdat je zelf heel goed moet begrijpen waar het landt en waaraan het bijdraagt. Anders loop je het risico verkeerde keuzes te maken. Dat doen we door in gesprek te gaan met de klant van de klant; de ‘voice of customer’ noemen we dat bij imec.”

Imec gelooft dat technologie – en vooral nanotechnologie – een belangrijke bijdrage kan leveren aan onze kwaliteit van leven. In veel domeinen, maar vooral in de zorg. Kathleen: “In de eerste plaats doordat we ziekte deels beheersbaar kunnen maken. Bijvoorbeeld in geval van Parkinson of een herseninfarct. Met behulp van draadloze microchips kunnen we de hersenen beter in kaart brengen en heel gericht met stimulatie of medicatie ingrijpen. Dat is niet alleen lichamelijke winst, maar ook mentale. Wat we ‘patient to person’ noemen, betekent dat je met een aandoening toch weer actief kunt deelnemen aan de samenleving. Dat verrijkt mijn leven. Net zoals mijn telefoon, die mij een schat aan informatie en wereldbeelden geeft. Mens en telefoon zijn nu al – in figuurlijke zin – met elkaar versmolten. Dat gaat verder, die chiptechnolgie kan ook een verrijking zijn voor mijn lichaam als dat niet optimaal functioneert.”

‘Ik denk vooral vanuit de kwaliteit van leven, wat kun je daaraan toevoegen? Als ik nierpatiënt ben, dan is het voor mij heel betekenisvol dat ik die kunstnier’ geïmplanteerd krijg’ - Kathleen Philips

‘Stel collectieve waarden centraal’

Als we kijken naar de versmelting van mens en machine blijft het dus niet bij sciencefiction. Met welke ethische grenzen moeten we rekening houden? Melanie: “Nanotechnologie is een van de zogeheten NBIC-technologieën, oftewel mensverbeterende technologieën. Ze hebben de potentie om de wereld en ons mens-zijn ingrijpend te veranderen. Onze uitdaging gaat zijn om niet in individuen te denken, maar om ook te praten over de collectieve menselijke waarden die we willen waarborgen in onze samenleving. Je wilt niemand oplossingen onthouden, maar wel agenderen voor wiens probleem dit een oplossing is. Vaak val je terug op oude ethiek. Zo moet iemand zelf kunnen bepalen: het hoeft van mij niet, naast het recht er wel gebruik van te maken. Het gaat om de emancipatie van gewone burgers ten opzichte van experts. Bij Rathenau Instituut gebruiken we de term ‘technologisch burgerschap’. Dat houdt in dat burgers werkelijk zeggenschap hebben, samen kunnen doordenken welke technologie nodig is, en hoe die ontwikkeld en ingepast kan worden. Dus hoe de technologie mensen kan dienen, zonder steeds van de mens en de samenleving te vragen om zich aan te passen.”

Kathleen: “Ik denk vooral vanuit de kwaliteit van leven, wat kun je daaraan toevoegen? Als ik nierpatiënt ben, dan is het voor mij heel betekenisvol dat ik die kunstnier geïmplanteerd krijg. Als ik nu zeg dat we in de toekomst een chip in ons lichaam hebben om bepaalde functies te herstellen, dan klinkt dat misschien bedreigend. Maar dat ligt anders als mensen weten dat die chip bepaalde lichaamsfuncties kan herstellen, en dat ze hierdoor niet meer dagelijks grote hoeveelheden medicijnen hoeven te slikken. Ik merk wel dat door corona een aantal van die technologie-ethiekdebatten meer aan de oppervlakte zijn gekomen.”

Nieuwe mensenrechten

Zo’n vijf jaar terug kwam het Rathenau Instituut met het voorstel om twee nieuwe mensenrechten toe te voegen. Melanie: “Het eerste is het recht om niet gemeten, geanalyseerd of gecoacht te worden. Monitoring kan positief zijn, maar ook beperkend. Daarom vinden wij dat er ook plekken moeten zijn om niet gemonitord te worden. Daarnaast pleitten we voor het recht op betekenisvol menselijk contact. Bijvoorbeeld binnen de zorg, maar ook als de overheid een belangrijke geautomatiseerde beslissing neemt. Dit houdt ook in dat robots menselijke relaties nooit zouden moeten vervangen, alleen verbeteren. Ons advies is uiteindelijk overgenomen door de Raad van Europa. En sindsdien komt de discussie steeds weer terug.” Kathleen: “Dat menselijke contact is een belangrijk punt. Wij zijn ervan overtuigd dat je zorgpersoneel veel beter kunt inzetten dankzij technologie. Ik ga zelfs nog verder door te stellen dat nanotechnologie in mijn optiek de enige manier is om de zorg schaalbaar te maken en de focus weer terug te krijgen op de arts-patiëntrelatie, specifiek voor taken die je niet met een chip of technologie kunt oplossen.” Melanie: “Je moet het bewust inzetten voor mensen die daar baat bij hebben, technologie in dienst stellen van de mens. Dus kijken met de professionals in de zorg waar je waarde kunt toevoegen. Die technologie kan die dokter niet vervangen, maar hij kan die dokter wel instrumenten aanreiken die anders niet beschikbaar zijn.”

‘Bij Rathenau Instituut gebruiken we de term ‘technologisch burgerschap’. Dat houdt in dat burgers werkelijk zeggenschap hebben, samen kunnen doordenken welke technologie nodig is, en hoe die ontwikkeld en ingepast kan worden’ - Melanie Peters

‘Een betere kwaliteit van leven’

Tot slot: wat is het ideaalbeeld van Melanie en Kathleen voor onze samenleving met digitale technologie over 20 jaar, wat is hun moonshot? “Nanotechnologie zal dan een cruciaal onderdeel zijn van de oplossing voor wereldwijde uitdagingen en vooral op het gebied van gezondheid”, stelt Kathleen. “Met nanotechnologie zijn we straks niet alleen in staat om functies te herstellen, maar ook om menselijke capaciteiten en eigenschappen te verbeteren of aan te passen. Ik zie een betere kwaliteit van ons dagelijks leven.” Ook Melanie ziet veelbelovende toepassingen van nanotechnologie: “Bijvoorbeeld in de stadslandbouw en lokale voedselproductie, voor het optimaliseren van oogsten. In de energiesector, om onderling vraag en aanbod op elkaar af te kunnen stemmen. Ik geloof ook in ‘citizien science’ waarbij technologie ons gaat helpen om kennis te delen. In plaats van topdown dashboardmodellen waarin de overheid onze data verzamelt, kunnen we weer zelf over onze data beschikken. En, ik zou imec willen uitdagen om bij iedere innovatie de vraag te stellen: wat is het onderliggende probleem, wat proberen we op te lossen? Want zoals Gerhart Rathenau al in zijn tijd constateerde: we vergeten soms nog weleens dat technologie niet alles gaat oplossen, maar het gaat ook niet alles in de war schoppen.”

In Memoriam: Melanie Peters

Met grote droefheid hebben wij kennis genomen van het overlijden van Melanie Peters, directeur van het Rathenau Instituut, op 11 augustus. Slechts enkele maanden geleden hadden we het genoegen Melanie voor dit Moonshot artikel te interviewen, samen met Kathleen Philips, General Manager van imec binnen het Holst Center. Met veel passie en energie benadrukte Melanie het menselijke en sociale aspect van technologie: “Ik word gedreven door de emanciperende verantwoordelijkheid die ik voel ten aanzien van technologie. Dat het voor ieders belang wordt ingezet, zodat innovatie nooit haar maatschappelijke doel voorbijschiet.”

Onze gedachten gaan uit naar haar familie en naasten.

Over Melanie Peters

Dr. ir. Melanie Peters is directeur van het Rathenau Instituut. Ze heeft een brede achtergrond in wetenschap, bedrijfsleven en de publieke sector. Peters is opgeleid tot levensmiddelentechnoloog en erkend toxicoloog, en gepromoveerd op het terrein van de biochemie. Na onderzoeksfuncties aan de universiteit van Texas en bij Shell, werkte ze in diverse bestuursfuncties voor het Ministerie van Landbouw, de Consumentenbond en Studium Generale Universiteit Utrecht.

Over Kathleen Philips

Dr. Kathleen Philips is VP R&D en General Manager van imec Nederland, onderdeel van Holst Centre. Ze is gepromoveerd in elektrotechniek, is auteur en co-auteur van meer dan 60 papers en bezit verschillende patenten. Philips kwam in 2007 bij imec waar ze onder meer hoofdwetenschapper was en toonaangevende research programma’s leidde op het gebied van Internet of Things. Voor imec was ze ruim 12 jaar wetenschapper bij Philips Research.

Dr. ir. Melanie Peters is director of the Rathenau Instituut. She has a broad background in science, business and the public sector. Peters is trained as a food technologist and recognized toxicologist, and holds a PhD in biochemistry. After research positions at the University of Texas and at Shell, she worked in various board positions for the Ministry of Agriculture, the Consumers' Association and Studium Generale University Utrecht.

Dr. Kathleen Philips is VP R&D and General Manager of imec Netherlands within Holst Center. She has been promoted in electrical engineering, is author and co-author of more than 60 papers and holds several patents. Philips joined imec in 2007 where she was chief scientist and led leading research programs in the field of Internet of Things. Before imec she was a scientist at Philips Research for over 12 years.

Published on:

28 May 2021