Introduction

“The essence of a smart city is not that it is crammed full of new technology,” says Pieter Ballon, smart cities expert and director of imec-VUB-SMIT. “First and foremost it is a city in which the quality of living has been lifted to a new level, fulfilling the practical needs and expectations of the people who live there.” With Kathleen Philips, program director perceptive systems at imec and Holst Centre, he explains how imec is working with the city council and a number of committed companies to make the city of Antwerp a living lab that may become a benchmark for urban environments worldwide.

Evangelize and build gateways

“The goal of our ‘City of Things’ project is to examine how a smart city can be developed as part of a realistic framework – working in close collaboration with the residents and the city council,” says Pieter Ballon. “Over the past year we have laid the foundations for doing that, both in terms of the organization and of the technology to support this smart city.”

A first requirement for the success of a complex project like this is to make sure all the stakeholders are on the same page. “You need to evangelize a lot for that to happen,” says Pieter Ballon, “You have to make sure that everyone is given the same level of expertise so that at the end of the day they feel the same about it. Part of that process involved my book, which was published in 2016 and is already in its fourth edition. So the topic is very much alive in Flanders. My aim was to enthuse the policymakers, while at the same time ensuring that every city didn’t start crafting its own solution. Because when that happens, everything gets fragmented, with systems that don’t talk to each other and cities that spend years tied to certain solutions and suppliers.”

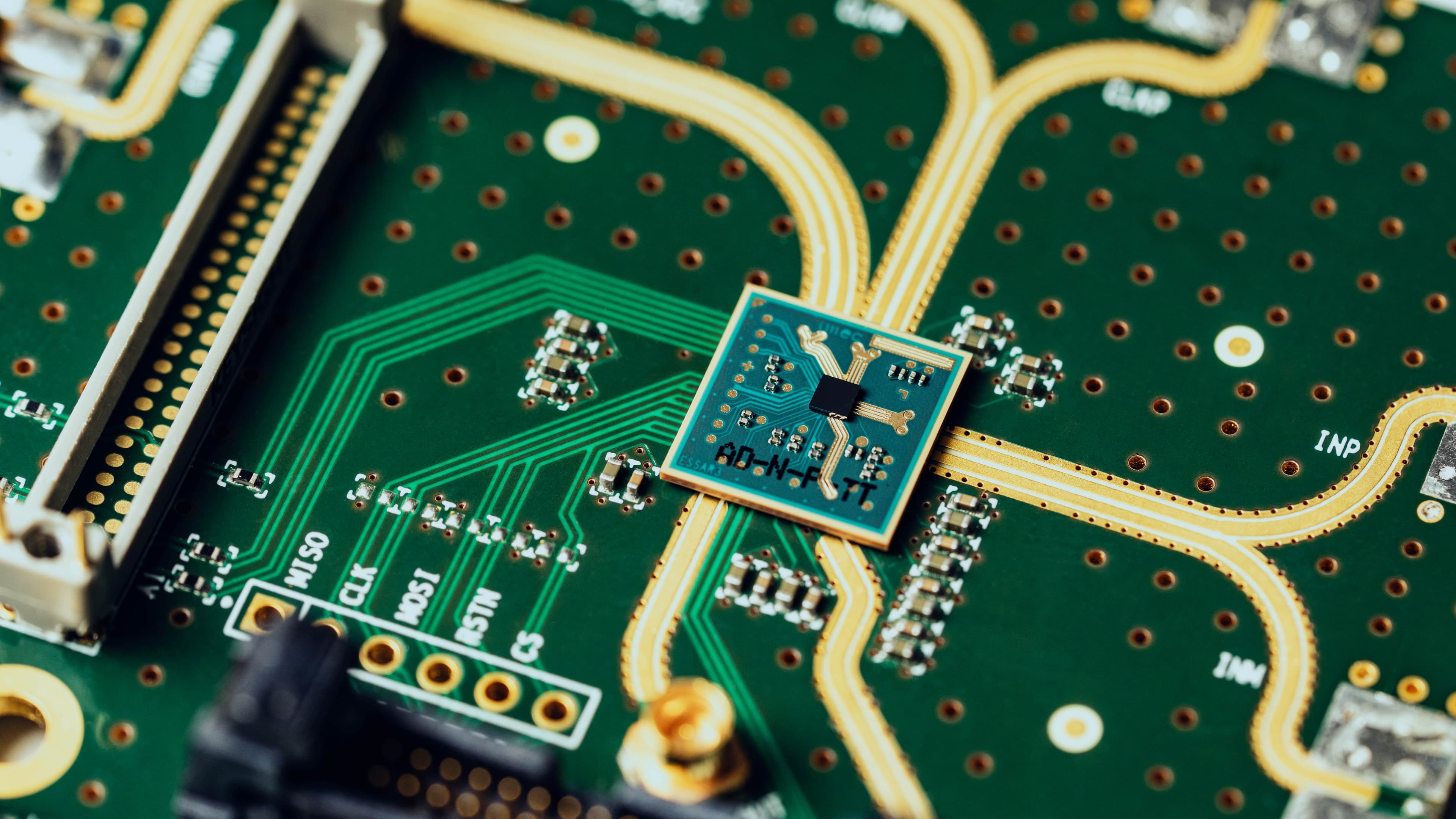

Once the project is up and running, 100 gateways will have been put in place across Antwerp. These will literally be the digital entry gates to the city and its inhabitants, complete with supporting technology. Gateways through which tens of thousands of wireless sensors, worn by the locals or attached to vehicles, the traffic infrastructure or buildings, can send their data to a whole range of applications. At the moment, we already have around 20 of these gateways in operation. The rest will be installed gradually. Everyone will be able to use them to develop or evaluate a specific smart application. The technology is heterogeneous, not based on a single solution or protocol, but on a series of standards that are suited to these applications, such as Zigbee, WiFi, Cellulair, LoRa, SigFox and others.

Senses for the city

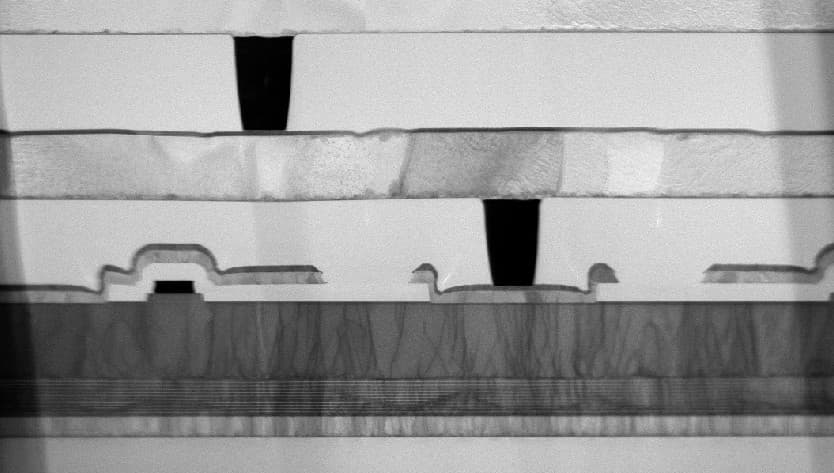

“Imec specializes in making environments smart, so we have also incorporated some of the technology that we have developed,” says Kathleen Philips. “For instance, there are currently two Belgian Post Office vans going about their business every day around Antwerp equipped with our wireless multi-parameter sensors. These can now take readings for around 20 parameters, such as CO2 and NO2. And soon they will be able to measure fine pollution particles. The aim is to arrive at more refined measurements, with hundreds of sensors installed all over the city, aboard a larger number of vehicles driving around. These readings can be linked to weather forecasts and knowledge of the local terrain and mobility. Eventually, they should make for a very detailed map of the city indicating e.g. air quality down to the level of street corners.”

“Other technologies that fit in with this scenario are our new ion sensor and 60 GHz wireless backhaul. The first of these, the ion sensors, have already been installed at a water pollution sampling station in the river Scheldt. The 60 GHz solution for backhaul networks will be developed to expand the available communication bandwidth quickly and seamlessly when major events are being staged or emergencies occur.”

The sensors and gateways are only a first layer, the senses of the smart city. Behind it all is an infrastructure for processing and analyzing big data in real-time. Like the gateways, this infrastructure is also technology-neutral and offers everyone who wants to use it a set of tools for converting data into useful knowledge. Kathleen Philips: “Take the sensor data relating to air quality. One of the scenarios we are considering for 2017 is an app for cyclists and pedestrians indicating the healthiest and safest route to a particular location.”

Changing behavior

All of this infrastructure will only form the foundation of the new digital city. To make it really smarter and more pleasant, the inhabitants will have to be involved. That is why the project will be recruiting a large number of volunteers from 2017 on. These will be put to good use, taking part in test panels that evaluate and gradually improve the new applications at every stage of their development – from initial idea to prototype. That way the city will become a genuine living lab.

Pieter Ballon: “In 2017 we intend to further expand this ‘Living Lab’ approach. Until now we have been asking people how they use a particular application and what they think about it. And we ask them whether they would be prepared to pay for applications (and how much). But now we want to test whether – and how – we can influence people’s behavior using applications. How can a smart app encourage people to behave more sustainably or more healthily? And how can it do that without forcing them or taking some of their comfort away? This type of behavioral change is the basis for many new business or governance models: the so-called outcome-based economy. It will also be one of the big challenges facing us in the years ahead.”

In the meantime, the government has already taken up some of the ideas and concepts of our experts. In 2017 one of the tasks given to imec is to work on the standards for open data, as well as on the first pilot projects for a smart Flanders. “This does not mean that all cities are required to implement the same policy,” says Pieter Ballon. “It simply means that everyone is given a number of tools that support their own policies and areas of emphasis in a smarter way.”

Living lab for the world

There’s an international component here, too: imec has been selected to take part in the European ‘Horizon 2020’ project called SynchroniCity. As part of the project, Antwerp will become one of the European reference zones, along with 6 other European cities. The aim is to establish large-scale pilot projects featuring experiments with new IoT services, based on the real needs of citizens. The Antwerp reference zone will focus mainly on mobility and logistics.

“We have set up this City of Things project from within iMinds, where we had a great deal of expertise in digital technologies, as well as in setting up large-scale living labs,” says Pieter Ballon. “But now that we are part of the major global player that is imec, the whole story can take on a far greater dynamic. We were a pioneer in this area in Flanders, working to harmonize things from an organizational and technological point of view. But it was still on a fairly small scale – especially if we look at the challenges facing large conurbations worldwide. Now, with imec, our approach can attract an international following. That is one of the breakthroughs – plus the fact that we can also call on truly innovative solutions for both the software and hardware layers of our solution.”

“All around the world there are many smart city initiatives going on and the challenge there is to differentiate yourself,” adds Kathleen Philips. “Yet in the past year in discussions with partners, people have said that they are very interested in our particular approach. This has to do mainly with the breadth of our approach, with us working on open technological innovation in a living lab, while at the same time also on applications, scenarios, business models, social organization and awareness. We are the only ones doing that for the time being.”

Pieter Ballon is a director of imec-VUB-SMIT and professor at VUB Brussels (Belgium). Pieter specializes in living lab research, business modelling, open innovation and the mobile telecommunications industry. He has been involved in numerous local and international R&D projects in this field, and has published widely on these topics. Currently, he is international Secretary of ENoLL, the European Network of Living Labs. Pieter holds a PhD in Communication Sciences and a MA in Modern History.

Kathleen Philips is program director at imec and Holst Centre for infrastructure and person-centric focused Perceptive Systems. Kathleen joined imec in 2007 and has held positions as principal scientist, program manager for ULP Wireless and program director for Perceptive Systems. Before that, she was a research scientist at Philips Research for over 12 years. She holds a PhD in electrical engineering, has authored and co-authored over 60 papers and holds various patents.

Published on:

1 January 2017